This project is a work in progress.

Genre: Alternate reality game

Platform: Multimedia, browser-based

Engine: Browser-based, Tumblr, Google Forms, Mapotic

Team: Solo

Duration: Aug 2024 - Present.

Roles/Contribution

Systems Designer: game loop, technical frameworks, puzzle creation

Visual Designer: logo and site design

Narrative Designer: story & lore design

Programmer: website design

The Berkeley Experimental Craft Society (BECS) is a self-sustaining Alternate Reality Game (ARG) that blends reality and fiction through collaborative storytelling, puzzle-solving, and creative expression. By empowering players to shape the narrative and game world, BECS fosters community engagement and participatory design, creating a sustainable framework for creative collaboration across various settings.

My thesis project as a Master of Design at UC Berkeley.

Showcased at:

Please note: The website, experimentalcraftsociety.com, is currently under construction due to a domain switch. It should be up & running again soon! For now, you can visit experimentalcraftsociety.myportfolio.com

The Experimental Craft Society website - this is under construction & being moved to experimentalcraftsociety.com

As an interactive and immersive platform, the Berkeley Experimental Craft Society (BECS) invites players to work together, solve challenges, and develop their own folklore within a fictional framework, enhancing their creative skills and ability to work in teams. ARGs are particularly suited for this purpose due to their unique blend of reality and fiction, designed to blur the boundaries between player interaction and storytelling. This approach not only aligns with the principles of design thinking - emphasizing iteration, problem-solving, and user experience - but also reflects the increasing integration of multimedia narrative, digital technology, and community-building in modern design practices and entertainment.

The Berkeley Experimental Craft Society (BECS) is represented by two key artifacts: a flexible framework for Game Masters (GMs) to build self-sustaining, co-created ARGs, and the BECS organization and narrative, an ARG implementation of the framework.

Design Process

Design goal: a self-sustaining ARG framework that eliminates the need for a central game master by allowing players to create the game as they play

Core loop: exploring and cultivating real-world community by identifying physical sites that players can transform through guerilla art installations, then submitting those sites for other players to comment on & transform

Narrative design: blending reality & fiction by layering co-created folklore; BECS provides the starting point while players fill in the details

Research & iterative design: The project went through many iterations, including an extensive literature review of prior ARGs (Jeff Watson's "Reality Ends Here" and "Mystery Flesh Pit" are foundational models for my academic exploration) as well as many playtests exploring the use of tradable tokens, physical clues, & roleplaying games. These form the basis of my ARG framework as what Watson refers to as "story facilitation" through a "systems-centric, bottom-up approach."

BECS ARG - based in reality, molded by imagination

The BECS ARG draws from a real Berkeley event: the 1985 nuclear reactor fuel cladding failure [1][2]. Fictionalized within the game, this incident creates a dimensional rift where good and evil forces emerge. Players, as members of BECS, ally with benevolent creative entities to preserve community balance by solving puzzles and creating art to reinvigorate “dead zones” with imagination. This mechanic links creativity with community well-being and encourages exploration of unique East Bay locations.

The BECS website introduces players to the crafting society, presenting typical projects like holiday card galleries. Interspersed among the art projects are Morse code clues hinting at the password to access the “Portal,” a locked page unveiling deeper BECS Zero lore.

Gameplay

Players can join the website as either a normal crafting club member or as a member of BECS Zero, the hidden society of players committed to restoring creativity to their local community by identifying creative "dead zones," i.e. areas requiring cleanup or guerrilla art installations to transform them. Players also identify Imagination Maintenance Locations, which are sites players have enhanced or documented for their artistic or unique qualities - these are typically places that were formerly dead zones.

All dead zones and Imagination Maintenance Locations are documented by players through the BECS Portal Reporting Form. Once submitted, a site admin can approve the report to be automatically uploaded to the BECS Zero Map, an interactive map that showcases all of the various player submissions.

BECS Portal Reporting Form, where players can submit reports of dead zones or Imagination Maintenance Locations

The BECS interactive map

Imagination maintenance takes form in many mediums. In one example, a player photographed a piece of pavement art on the UC Berkeley campus, tagged the location, and wrote an accompanying poem describing how the art supernaturally came to be there. In another case, a player uploaded images of art sculptures from a temporary street art show and tagged the location. This combination of real-life art exhibits and user-formed lore creates a sense of layered depth to the overarching narrative. The map acts as both a dynamic gameplay tool and a repository of player work and events. By documenting dead zones and consequently cleaning up the physical environment, players restore their local communities through playing the game.

Players communicate directly through the BECS Portal, where they can comment and share updates. While deeper discussions may occur offsite, centralized communication fosters collaboration and ensures participants stay informed about the evolving game world.

BECS Framework

A co-created ARG must evolve alongside its players, requiring a flexible framework. The BECS Framework offers a foundational guide for constructing such games:

Foundation

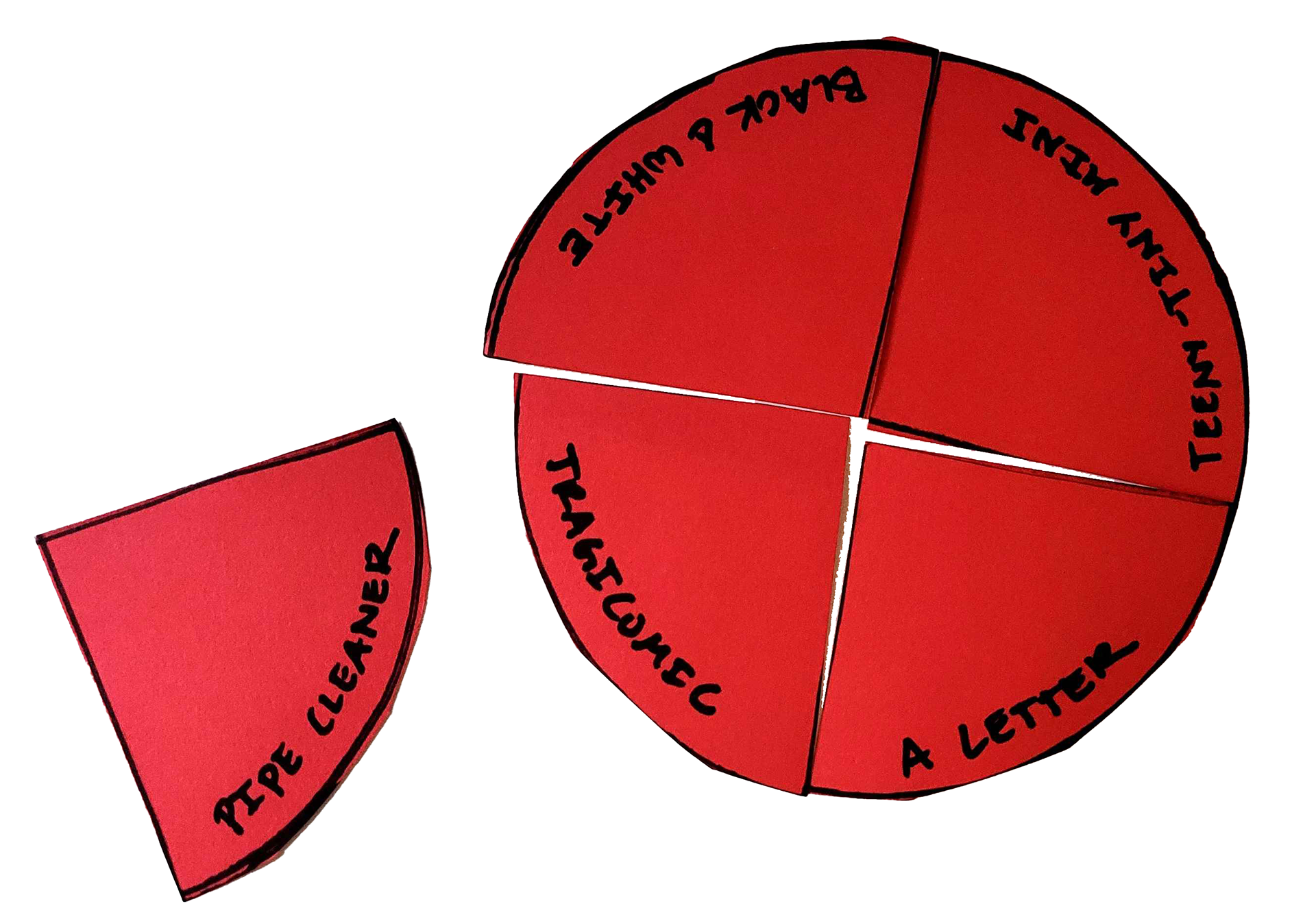

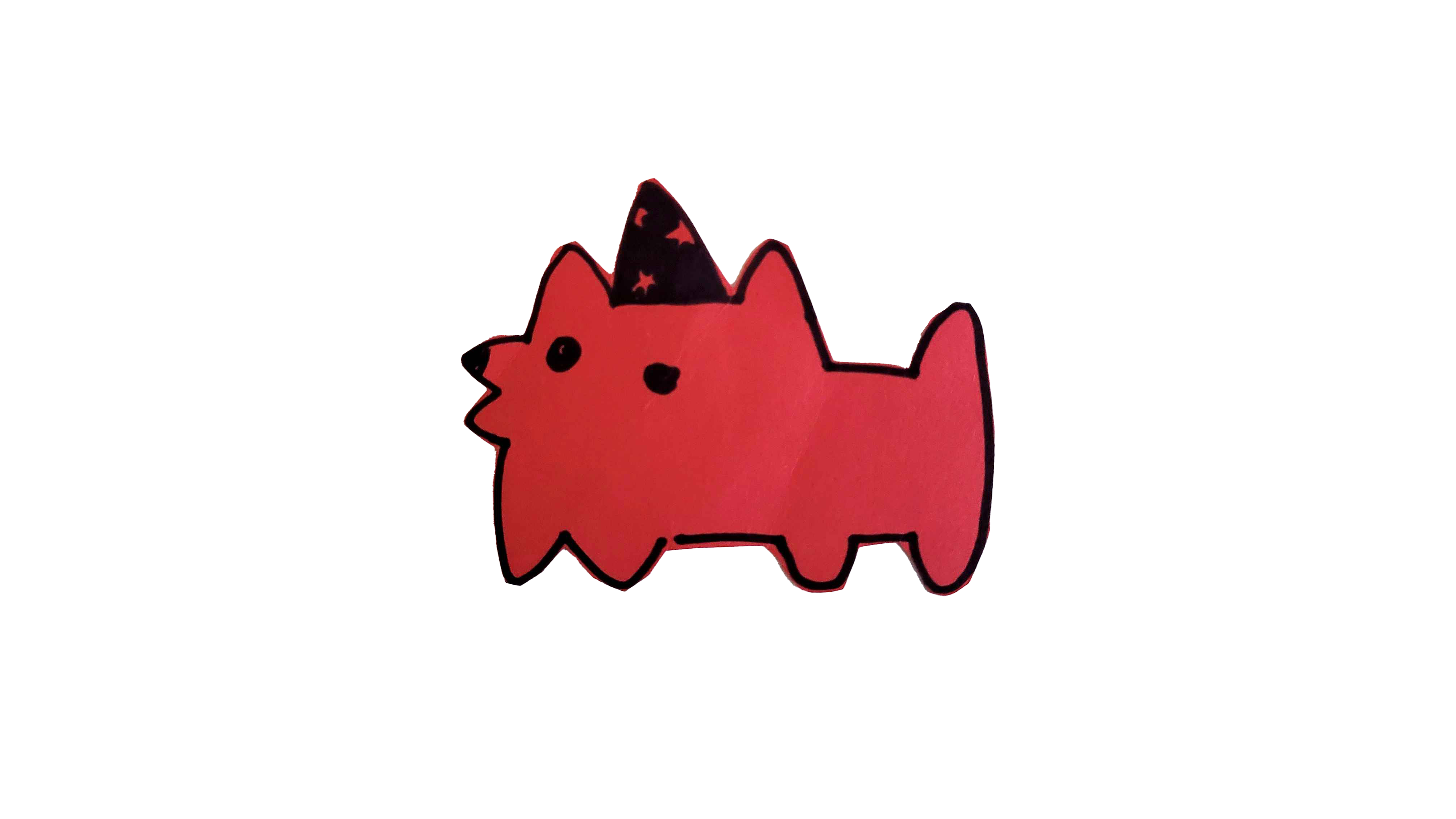

A core theme anchors the ARG and allows players to layer their imagination on top of reality through suspension of belief. During BECS, players thrived with a basic level of worldbuilding layered on top of physical reality (i.e. the humor of the Wizard Dog in a studio or the nuclear meltdown of the BECS ARG). The importance of building a world, rather than a story, cannot be overstated. By creating a world layered on top of our own without main characters or plot points, players are allowed to fill in the gaps and become their own protagonists.

A core theme anchors the ARG and allows players to layer their imagination on top of reality through suspension of belief. During BECS, players thrived with a basic level of worldbuilding layered on top of physical reality (i.e. the humor of the Wizard Dog in a studio or the nuclear meltdown of the BECS ARG). The importance of building a world, rather than a story, cannot be overstated. By creating a world layered on top of our own without main characters or plot points, players are allowed to fill in the gaps and become their own protagonists.

Entry Points

Entry points at multiple levels make the game accessible. The easiest is to establish an entry point within the foundation of the game, such as through a club, website, Instagram page, etc. These could include clubs, websites, or social media profiles. Familiar mediums with unusual text, visual aesthetics, or technical quirks draw attention as something out of the ordinary.

Entry points at multiple levels make the game accessible. The easiest is to establish an entry point within the foundation of the game, such as through a club, website, Instagram page, etc. These could include clubs, websites, or social media profiles. Familiar mediums with unusual text, visual aesthetics, or technical quirks draw attention as something out of the ordinary.

Tools for Co-Creation & Communication

Players must be able to contribute to the game’s lore. Allowing uploads, comments, or discussions on the foundational website or related platforms enables players to shape the game world collaboratively.

Players must be able to contribute to the game’s lore. Allowing uploads, comments, or discussions on the foundational website or related platforms enables players to shape the game world collaboratively.

Automation

Technical automation, like scheduled posts, sustains the game’s momentum even when the GM isn’t available.

Technical automation, like scheduled posts, sustains the game’s momentum even when the GM isn’t available.

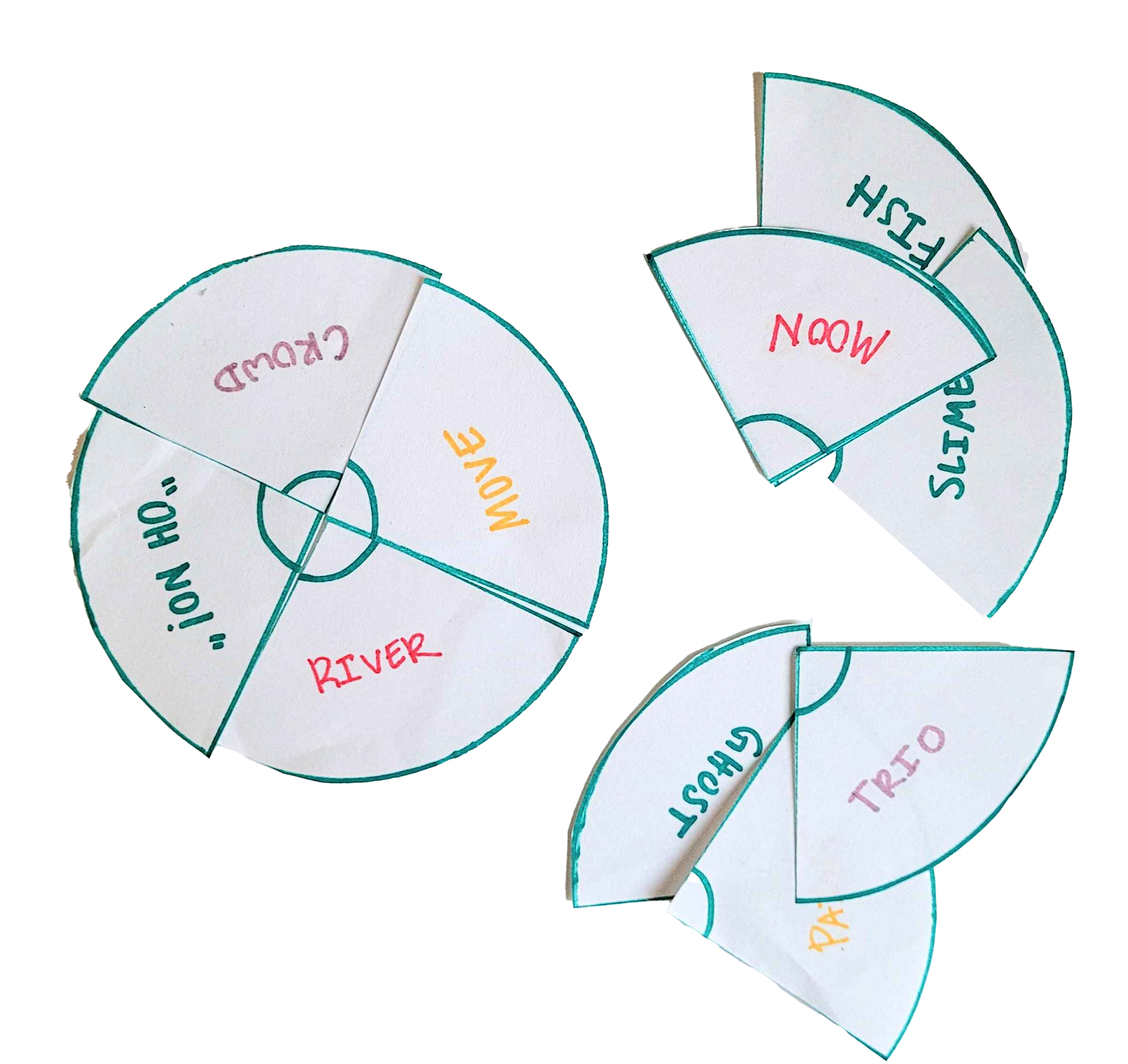

Early paper prototypes, playtests, and clues from the beginning of the ARG - experimenting with tradable tokens, cards, and physical clues left in key locations.

Players exchanged these to solve puzzles by creating collaborative art based on clues printed on their cards. Different prompts and clues on the cards had varying point values, so players were encouraged to exchange and combine cards to maximize their shared points. However, this was quickly scrapped due to the extensive effort needed to continuously design, print, and distribute cards to players, which was a very linear process that did not satisfy the sense of sustainable

co-creation between GM and player. Additionally, the focus on points led to some players hoarding cards in order to earn the most points individually rather than creating together.

co-creation between GM and player. Additionally, the focus on points led to some players hoarding cards in order to earn the most points individually rather than creating together.

While I was running the card game prototypes, I also explored what level of independence and self-sustainability the game could contain. One standout prototype was the “Wizard Dog,” a simple drawing of a dog with instructions on the back directing players to take an image of themselves with the Wizard Dog and post it to a Slack channel. If at least 25 participants complied, the Wizard Dog promised to “bless ye.” This tested whether a game could begin and conclude without direct intervention from its creator, relying entirely on participant engagement, as players had to pass the Wizard Dog among one another to play. It also evaluated whether participants would contribute creative content (photos) and the variety of submissions.

24 students, instructors, and faculty members participated in the challenge, just shy of the reward goal. Many community members also indirectly participated by leaving reactions and comments to the photo posts in the Slack.

The Wizard Dog took place in the Master of Design studio at UC Berkeley, where students are already familiar with testing one another’s prototypes, so while it isn’t representative of the greater public, it does suggest that players were willing to contribute some form of creative labor in exchange for an unspecified reward.

Conclusion

Implications for design: BECS demonstrates how ARGs can function as dynamic, community-driven experiences. The non-hierarchical co-creation model transforms players into active creators, blurring the line between participant and designer. This approach aligns with participatory design methodologies, emphasizing user involvement. By allowing players to shape stories, puzzles, and mechanics, the ARG deepens engagement while fostering a sense of collective ownership, sustaining the project even in the absence of a formal orchestrator.

Future work & challenges: Still in its early days, BECS has a lot of potential for growth. Intentionally obfuscated within a niche location & area (crafting club in Berkeley), player outreach is mostly through word of mouth. However, the few players that have solved the puzzles and engaged with BECS Zero are very dedicated. BECS is effectively a springboard for future ARGs to grow out of. It is not the final word on self-sustaining ARGs but a starting conversation - an invitation for others to join, critique, and build upon its foundation. Continued updates on the website as well as a balance between player-organized and GM-organized events may help the story grow.

New conversations & broader implications: BECS invites reflection on how ARGs can function in educational or professional settings as tools for team-building, creative collaboration, and self-expression. Could ARG frameworks replace traditional instructional or organizational models, fostering innovation through co-creation and player-driven narratives?

The collaborative nature of BECS also challenges traditional notions of authorship and narrative ownership. Unlike conventional storytelling with a singular narrative voice, ARGs embrace multiple canons, allowing stories to evolve organically through player contributions. This raises broader questions about the role of the creator and the audience in storytelling and whether such models could redefine narrative structures in other media.

Additionally, the interplay between knowledge dissemination and restriction within BECS reflects larger societal dynamics. Who is “in the know” and what restricts others from having that same information? As a fictional secret society, BECS embodies the allure of hidden knowledge, while its mechanics aim to subvert hierarchical barriers to information. However, its framing as a crafting club inherently narrows its appeal, attracting a niche audience. This duality prompts critical questions: In what circumstances can ARGs reflect the harmful properties of conspiracy theories by fostering exclusivity?

Conversely, can the blending of fiction and reality create spaces for marginalized voices to share information amidst censorship and restrictive environments?

Conversely, can the blending of fiction and reality create spaces for marginalized voices to share information amidst censorship and restrictive environments?